Last week I had a meeting with several local criminal-justice agency heads. One thing we discussed was their hiring needs, so I thought this would be a good time to discuss how someone qualifies for a job in law enforcement (there are plenty of other CJ jobs too, but the qualifications for those vary).

In every jurisdiction, the minimum criteria to become a police officer include a high school diploma (or GED) and a record clean of felonies. A driver’s license is usually mandatory too. Once upon a time, those things would have been enough to get you a job as a cop.

Nowadays, though, most agencies want more. Some want an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree. All of them will require a clean background check, which means not just lack of criminal activity but also good credit and good associates. Agencies will check candidates’ social media accounts. They may use a lie detector. They will also ask about drug use. Standards for this have shifted, but at least in my area, agencies won’t hire anyone who has ever used hard drugs or who has used pot within the past year or two (even though it’s now legal here).

In many states, applicants will be subject to a psychological evaluation. They’ll also be given a physical agility test and a test to evaluate their ability to communicate clearly in writing.

New police officers have to go through training, of course. Some agencies want new hires to have already completed the academy, but others, especially the larger ones, will hire people first and pay them as they go through the academy.

Last week the chiefs said their ideal candidate is someone who can pass the background check and tests, who has strong writing skills, who has CJ experience as an intern, and who shows a meaningful commitment to the community.

Right now almost every police agency in the US is desperate for strong candidates. The Las Vegas PD has 600 openings! During a recent trip to Vegas, I saw them advertising on the Strip. I don’t know what kind of applicants they think they’ll get from that.

This is a military jail (or gaol, I guess) in Edinburgh, Scotland.

This is a military jail (or gaol, I guess) in Edinburgh, Scotland. This jail cell is in Monterey, California. I think it’s interesting how closely it resembles the Scottish cell.

This jail cell is in Monterey, California. I think it’s interesting how closely it resembles the Scottish cell. These are the ruins of the gold rush-era jail in Coloma, California.

These are the ruins of the gold rush-era jail in Coloma, California. This gold rush jail is in better shape. It’s in Columbia, California. My younger daughter looks happy to be there, doesn’t she?

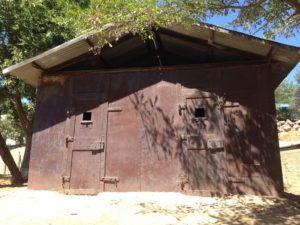

This gold rush jail is in better shape. It’s in Columbia, California. My younger daughter looks happy to be there, doesn’t she? This is also from gold rush times, and it’s in Knights Ferry, California. Summer temps regularly get above 100F there–imagine what it would be like locked inside those metal walls.

This is also from gold rush times, and it’s in Knights Ferry, California. Summer temps regularly get above 100F there–imagine what it would be like locked inside those metal walls.

This jail is in a tower atop the city wall in Ulm, Germany.

This jail is in a tower atop the city wall in Ulm, Germany. One of those flags is flying over a cell in the castle wall in Lisbon, Portugal.

One of those flags is flying over a cell in the castle wall in Lisbon, Portugal. This cell was in the old city wall in Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina.

This cell was in the old city wall in Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina. And this one (which contains my daughter in the photo) is in beautiful Dubrovnik, Croatia.

And this one (which contains my daughter in the photo) is in beautiful Dubrovnik, Croatia. Finally, another German cell, in Rothenburg.

Finally, another German cell, in Rothenburg. So here’s your plot bunny. Your character is an attorney representing a smooth bad guy. The bad guy lies on the stand—implicating someone else—and is found not guilty. Now the cops are after that third party, and your lawyer wants to make sure an innocent party doesn’t go to prison. What does he do? And what complications might ensue if he’s attracted to that innocent third party?

So here’s your plot bunny. Your character is an attorney representing a smooth bad guy. The bad guy lies on the stand—implicating someone else—and is found not guilty. Now the cops are after that third party, and your lawyer wants to make sure an innocent party doesn’t go to prison. What does he do? And what complications might ensue if he’s attracted to that innocent third party?