Last week I posted about potential plot bunnies when dealing with the undead. This week I’m expanding on the topic a bit.

Under common law, homicide is defined as the unlawful taking of a human life. While seemingly simple, that definition has occasionally led to some interesting legal questions. For example, is an unborn baby “human”? At common law, the answer was no, but many have argued that at the very least, fetuses that would be viable outside the womb should be considered human.

If you are an author of speculative fiction, I think you could play with this issue in a number of interesting ways. Sure, there’s the undead, such as zombies and vampires. But what about sentient creatures from another planet? What about artificial intelligence—does it achieve humanity when it becomes sentient and self-aware? What if a human is genetically modified? What if so many parts of her are replaced with artificial bits that she’s barely organic? We’re talking an entire warren’s worth of plot bunnies here!

Relatedly, we have the issue of what constitutes “taking of a life.” In reality, this has come up in cases where the victim was brain-dead but still on life support, and when he died many years later from complications related to the initial attack. But again, spec fic offers us interesting questions. What if the victim is resurrected? What if his body is destroyed but his mind or soul—some essence of him—is preserved in some way? What if he’s reincarnated?

I think the world is sorely in need of more spec fic legal procedurals!

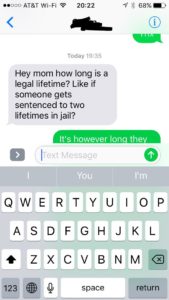

I think jailhouse lawyers could make a wonderful addition to a book. Maybe your hardened con redeems himself by struggling against all odds to prove someone else’s innocence or to improve prison conditions. If you’re considering this plot idea,

I think jailhouse lawyers could make a wonderful addition to a book. Maybe your hardened con redeems himself by struggling against all odds to prove someone else’s innocence or to improve prison conditions. If you’re considering this plot idea,