Okay. Once again, not to get political… but a certain son of a certain sort-of elected leader (sigh) claimed that the attorney-client privilege applied to certain phone conversations between him and his father. Neither of whom are attorneys. But, said Junior, it totally counts because Dad’s lawyers were listening in on the conversation.

Does Junior’s argument have any legal validity? Of course not. But let’s look at the privilege itself.

To take a step back, it’s important to know that, in general, a person’s conversations with another person may be used as evidence. This is true whatever the mode of those conversations: live in person, voice via telephone, electronic via text or email, etc. But there are a few exceptions to this rule, situations where those conversations are protected and where the opposing side cannot “discover” them (i.e., force the other side to hand them over). These exceptions—or privileges—include conversations between physicians and patients, between clergy and penitents, between accountants and clients, between spouses, and between lawyers and clients. Each of these has special rules; today I’m just addressing the final one.

The primary purpose of the rule is to allow clients to be frank with their lawyers, which in turn allows lawyers to be more effective at defending them. In order for the privilege to apply, at least one of the people must be a lawyer, the other person must be that lawyer’s client (or seeking to become one), and the conversation must be about legal matters. Therefore, although I’m a lawyer, a friend who casually chatted with me about his plans for the next day would not be able to invoke the privilege to protect that conversation. And just because Dad’s lawyers were listening to a conversation doesn’t mean the privilege can be invoked.

Even when the privilege applies, there are exceptions. One interesting exception is that it generally can’t be used if one or more parties uses the information to commit a crime. For instance, if Bruce asks his lawyer, Tina, how best to cover up the fraud he plans to commit, that discussion isn’t privileged.

Another twist has to do with perjury. If, because of conversations with the client, the lawyer is aware of the truth of the situation, but then the client lies about those facts on the stand, the lawyer may have the ethical duty to rat him out to the judge. Thus, a lawyer may get caught between her duties to the defendant and her duties to the court. Plot bunny! (Many lawyers handle this situation by refusing to let a client take the stand if they believe the client will perjure himself.)

Furthermore, a client can waive the privilege and voluntarily choose to share privileged communications. Simply discussing the conversation in public constitutes a waiver.

Another exception to the privilege is especially pertinent to Junior’s situation. The privilege is nullified if anyone aside from the attorney and client was present during the conversation. Such as, say, a Russian lawyer who had neither father nor son as a client.

Of course, if certain sons of certain leaders can be this clueless about how the privilege works (or at least pretend to be), so could your characters. So feel free to make this a plot point, if you wish.

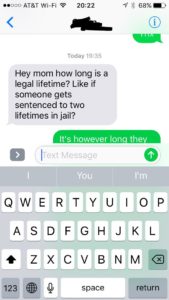

I think jailhouse lawyers could make a wonderful addition to a book. Maybe your hardened con redeems himself by struggling against all odds to prove someone else’s innocence or to improve prison conditions. If you’re considering this plot idea,

I think jailhouse lawyers could make a wonderful addition to a book. Maybe your hardened con redeems himself by struggling against all odds to prove someone else’s innocence or to improve prison conditions. If you’re considering this plot idea,